polish school of poster

- Alicja Wlaszczuk

- Feb 17, 2021

- 9 min read

Okey, I know I know, this was originally written as my essay for uni. But! It is still a huge source of inspiration for me so here we go, have a nice read!

Short history of Polish School of Poster few stories of its creators.

Figure 1 - J.Mehoffer, 1899, National Museum in Cracow

“Polish School of Poster” is a hard to define, controversial art movement, that years later still often sparks a discussion. Even art historians often have conflicting opinions on how to define it and where the term itself comes from (Giżka, 2006). For many who are familiar with it, the movement will be synonymous with its glory years of film poster designing, falling between the 50s and 70s (Pluta, unknown year). This assumption is not entirely false since during this time frame the most prominent artists were active and busy with creating their famous artworks. In this essay however, I want to tell a story beginning with the very first known Polish posters created at the turn of twentieth century by Young Poland’s artists such as Stanisław Wyspiański or Józef Mehoffer, who are now thought to be the cornerstones of Polish poster design. I will also try to explain how political turmoil and cultural isolation influenced the creation of a completely unique style of posters, allowing them to stand out on the European poster design scene of last century and is characterised by an almost complete lack of rules (Zwolinska, May 2018).

Figure 2 - S. Wyspiański, 1898, „Wnętrze”, National Museum in Warsaw

Towards the end of nineteenth century, Poland was still divided under the control of Russia, Austria and Prussia after The Partitions that happened over one hundred years prior. That is when new, relatively cheap ways of colour lithography, recently invented in France, revolutionised print throughout Europe. These new techniques were also introduced to bohemian Cracow and posters became a new medium of art as well as tool of communication (Austoni, 2010). Not being able to live in an independent country, Polish artists at that time were trying to create works of art that would resonate with Polish audiences. Poster makers were usually already recognisable in artistic environment, as accomplished painters, who took up a newly introduced medium. Thus, the posters created were mainly targeted to inform about various cultural and art-themed events. To keep patriotic spirits up and motivate to fight with the occupant they incorporated national motifs and symbols (Zwolinska, May 2018). Those folklore elements were mixed with popular art styles of the period, such as Japanism and Secession, which lead to the creation of posters with high artistic and aesthetic value. Great example of mixing the styles together is Józef Mehoffer’s poster for Furniture Lottery for Matejko’s flat (Fig 1). Another poster worth mentioning was created by Stanisław Wyspianski (who was also an important playwriter and poet) for a theatre play “Wnętrze” (“Interior”), picturing young girl looking out the window. This one is especially important since it is considered to be the first one classified as an artistic poster and not just an informative affiche (Fig 2). Since that moment artists played freely with the form, blurring the lines between illustration and typography. Not long after that, poster became a popular and desirable art form. This led to the first International Exposition of Poster to be held in Cracow in 1898 (Austoni, 2018).

Poland regained independence and become whole again in 1918, after World War I. Because it was no longer under the rule of three different countries, cultural development lasting a century was taking place mainly regionally, not nationally. Thus, during the rebuilding of national identity, emphasis was put on reconstructing feeling of solidarity between all Polish people, no matter what regime they lived under before. Posters were one of the tools used for that purpose. They were easy to understand and did not require fluency in Polish. The latter was especially important, because during annexation, in many places it was illegal to speak Polish and huge number of people lost the ability to use their own native language. Posters were serving mainly social or political purposes, often encouraging people to vote, properly educate their kids or take part in routine doctor check-ups (Fig 3). Posters of a similar style were also used to advertise everyday products (Fig 4) (Zwolińska, June 2018).

Figure 3 - T. Gronkowski, 1929, Poster encouraging people for cancer screening tests.

Figure 4 - T. Gronkowski, 1931, Poster advertising cigarettes

Shortly after World War II, private companies, such as publishing houses, were closed under the rule of Socialist People’s Republic. The communists wanted to redefine new cultural and artistic standards. This caused previously popular poster styles, which were heavily inspired by French artists, to be completely rejected as too “bourgeois”. The topic of posters also changed. Instead of advertising consumer goods, posters were now mainly used as a tool of political propaganda used only by government, therefore poster designers lost majority of their independence. In 1947 Henryk Tomaszewski, who graduated from Warsaw’s Academy of Arts in 1939, started his poster making career for a film distribution agency accompanied by small group of fellow artists. They were limited by lack of proper equipment as well as censorship. As Tomaszewski admits himself in Victore’s article (1995, p.34) “We had absolutely nothing to work with. No materials. No brushes. No paint. Hardly any paper. We got powder paint from the corner shop. And the patterns we cut with scissors”. Tomaszewski is frequently called a ‘father of Polish poster’. He was one of the creators of new modern style of poster, using bold colours, clashing patterns and collage (Fig. 5) (Fig.6). He also was a mentor figure for many other acclaimed poster artists, like Roman Cieślewicz or Jan Lenica (Victore, 1995).

Figure 5 – H. Tomaszewski, 1947, Poster for the film ‘Odd Man Out’

Figure 6 - H. Tomaszewski, 1957, poster for the film Adventures of Pat and Patachon

In 1953, Poland got to enjoy a little bit of liberation after Stalin’s death. This allowed foreign movies and plays to be introduced more freely and widely. Jazz also gained popularity and Warsaw’s Autumn International Festival begun in 1956 (Schubert, 2001). As Konorowski states in his article (2017, p.68) some of the changes were aimed to warm up Poland’s appearance abroad and minimise the cultural gap between countries behind The Iron Curtain and the rest of the world. Posters designed for this occasion, however, were not exactly in line with canon of the whole movement, which usually went for advertising more entertainment-oriented art for masses, like film. Majority of posters advertising Warsaw Autumn Music Festival were usually created by acclaimed artists, who amazed international publicity with their almost anarchic freedom of expression, not often seen abroad. They were not hesitant to break all the conventical rules of design, letting their personality and style scream. This approach to personal expression was the key element of the design, sometimes even compromising readability. Those posters were not supposed to depict the topic directly. Instead, it was more about capturing the feeling and associations that come to mind. A good example of this is Waldemar Świerzy’s poster (Fig 7) for 1967 Warsaw Autumn which depicts rhythmic lines with one visible point of distortion that breaks the pattern, creating illusion of third dimension (Konorowski, 2017).

Figure 7 - W. Świerzy, 1967, Poster for Warsaw Atummn 1967

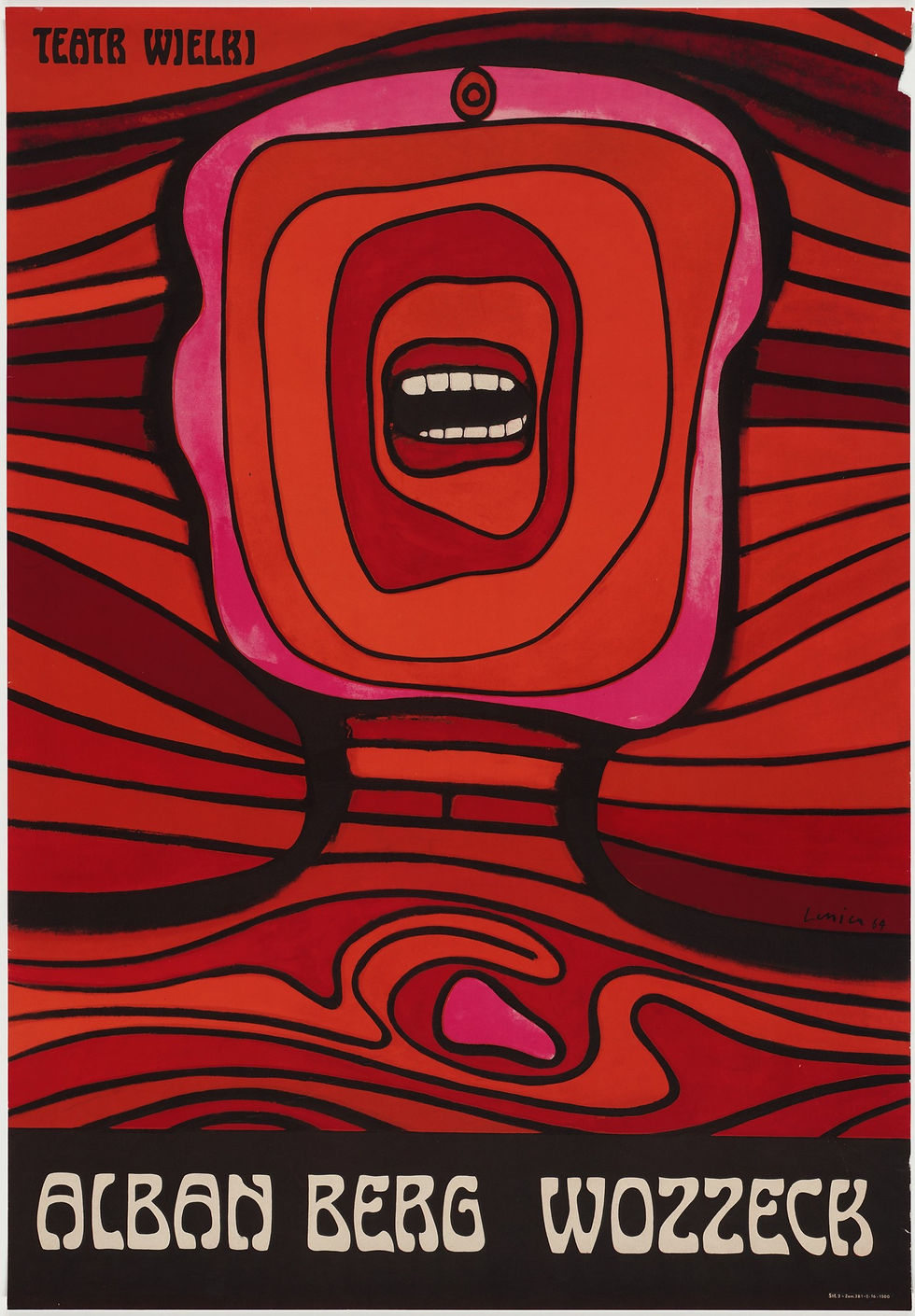

Posters of the early 1960s were even more focused on personal direction and artistic freedom than ever before. It was sometimes more important how the poster was telling a story, than what the actual message was. The aim was to make poster an independent form of art (Zielinski, 1994). 1960s werealso a decade when most recognisable poster makers were active. One of them was Jan Lenica. A former architecture student who, in the 50s, became Henryk Tomaszewski’s assistant at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts. From early on during his career, he was interested in satirical drawings, but what brought him fame and international recognition, was his skills in poster making as well as animated films. (Fig 8) His posters were heavily influenced by Art Nouveau, with flowy, curvy lines and simple forms, which often lacked details and made use of a monochromatic colour palette. Lenica was not scared to use traditional techniques to create his works. Another characteristic trait of his posters was lack of perspective or background. However, what was never missing, was his amazing talent of poetic metaphors and use of irony and absurdity to catch viewers’ attention. He often worked with watercolour, gouache or tempera on paper (Grządek, 2004). What also is interesting about Lenica, is the fact that he is thought to be an author of the term “Polish School of Poster”, which he first coined in Swiss magazine “Graphis” in 1960.

Figure 8 - J. Lenica, 1964, Poster for theatre play "Wozzeck"

Another worth mentioning artist of the period was Roman Cieślewicz. According to article “The double lives of Roman Cieslewicz”, the artist worked both sides of Cold War, but what remained his motivation was his desire to communicate. Now known mostly for his film and theatre play poster commissions, he was also working as an art director for women’s magazine “Ty i Ja” (“You and Me”). Regardless of many technical and financial limitations, he was able to deliver spreads of high artistic value. In 1963, he was invited to Paris by Elle’s art director – Peter Knapp – and started work for the magazine, while still continuing to send designs for “Ty i Ja” back to Poland. Alongside his editorial work in Paris, he was creating posters, often expressing his political beliefs. Cieślewicz was recognisable for his characteristic poster making style, using mixture of type, texture and illustration. He also was no stranger to the art of collage and was fascinated by surreal possibilities created by using this technique. A good example of this practise is his poster (Fig 9) for play “Forefather’s Eve” written by Adam Mickiewicz, depicting human figure made of dry soil with lava in a place of heart. This refers to famous quote from the play saying that the nation is like lava – cold, dry and tough on the outside, with nothing being able to cool down the heat of its inside

Figure 9 - R. Cieślewicz, 1967, poster for play "Forefather's Eve"

(Anonymous, 2010).

Despite being often criticized nowadays for its lack of artistic direction and putting more focus on artistic expression, rather than clear communication or readability, Polish poster was undoubtfully a good representation of country’s identity. According to George’s article (2018) Stalin once said that trying to impose communism on Poland was “as absurd as placing saddle on a cow”. Poles made sure to protect their own cultural heritage and, despite limitation, incorporate it in producing modern artworks. Hence, out of all counties of The Eastern Block, Poland was probably the one with most autonomy. George also quotes Konorowski, who says that despite all the restrictions and repressions “there was always typical Polish spirit of contrariness, insubordination, non-compliance and anarchy” (George, 2018). Many other experts of the field say that this exactly is the reason why Polish poster gain so much worldwide recognition. Schubert, during his interview with Pieczek, claims it is the spontaneity, unlimited by rules of creativity and the creation of space for artists to work intuitively, that helped to earn international recognition (Pieczek, 2018). Even though many say Polish School of Poster died in 1989 when Poland underwent systemic transformation, I personally think that even now, many years after its peak, young artists are trying to maintain national tradition of witty, simple poster that would catch your eye (Fig 10, ‘konstytucja’ – constitution, ‘ty’ – you, ‘ja’ - I).

Figure 10 - Luka Rayski, 2017, "Constitution" politicial poster

References:

Anonymous, 2010, The double lives of Roman Cieslewicz, Creative Review

Giżka, S., 2006, Polska Szkoła Plakatu. Available at: https://culture.pl/pl/artykul/polska-szkola-plakatu, accessed: 11.01.2021

George, C., 2018, Discover the underrated art of Polish poster design. Available at: https://www.sleek-mag.com/article/polish-poster-design/, accessed: 12.01.2021

Konorowski, M., 2017, Between Connotation and Denotation. Posters Announcing the Warsaw Autumn International Festival of Contemporary Music in 1956-2015, Musicology Today, 14 (1), 67-74

Pieczek, U., 2018, interview with Schubert, Z., Kiedy plakat śpiewał po polsku, Znak. Available at: https://www.miesiecznik.znak.com.pl/kiedy-plakat-spiewal-po-polsku-zdzislaw-schubert-polska-szkola-plakatu/, accessed: 09.01.2021

Pluta, E., unknown year, interview with Joostberens, Polska Szkoła Plakatu. Co z niej pozostało?. Avaliable at: https://www.swps.pl/strefa-designu/blog/19951-polska-szkola-plakatu-co-z-niej-pozostalo, accessed: 08.01.2021

Victore, J. 1995, Poster master, Print (Archive: 1940-2005), 49 (5), 32-41

Zielinski, F., 1994, The rise and fall of governmental patronage of art: a sociologist’s case study of the Polish poster between 1945 and 1990, International Sociology, 9 (1), 29-41

Zwolińska, I., 2018, Początki plakatu polskiego: Z ulicy na salony – o historii I procesie kształtowania się tej formy graficznej. Available at: https://grafmag.pl/artykuly/poczatki-polskiego-plakatu, accessed: 15.01.2021

Zwolińska, I., June 2018, Polski plakat na początku XX wieku: sztuka łącząca roozbity kraj. Available at: https://grafmag.pl/artykuly/polski-plakat-na-poczatku-xx-wieku-sztuka-laczaca-rozbity-kraj, accessed: 22.01.2021

Bibliography:

Anonymous, 2010, The double lives of Roman Cieslewicz, Creative Review

Austoni, A., 2010, The legacy of Polish posters. Available at: https://www.smashingmagazine.com/2010/01/the-legacy-of-polish-poster-design/, accessed: 11.01.2021

Boczar D. A., 1984, The Polish poster, Art Journal (U.S.A.), 44 (1), 16-27

Bourton, L., 2019, Symbols of freedom “and the struggle for it”: a look at the Polish School of Poster. Available at: https://www.itsnicethat.com/articles/projekt-26-polish-school-of-posters-graphic-design-211019, accessed: 26.01.21

Brooke, M., 2010, Not like they do it in the west, Sight and Sound, 20 (4), 12-13

George, C., 2018, Discover the underrated art of Polish poster design. Available at: https://www.sleek-mag.com/article/polish-poster-design/, accessed: 12.01.2021

Giżka, S., 2006, Polska Szkoła Plakatu. Available at: https://culture.pl/pl/artykul/polska-szkola-plakatu, accessed: 11.01.2021

Grisham Gimm, E., 2001, Polish artists: Transcending cultural and political stereotypes, Dialogue, 24 (3), 31-34

Grządek, E., 2004, Jan Lenica: Visual Arts. Available at: https://culture.pl/en/artist/jan-lenica, accessed: 25.01.21

Konorowski, M., 2017, Between Connotation and Denotation. Posters Announcing the Warsaw Autumn International Festival of Contemporary Music in 1956-2015, Musicology Today, 14 (1), 67-74

Krampen, M., 1984, The semiotics of Polish poster, The American Journal of Semiotics, 2 (4), 59-82

Pieczek, U., 2018, interview with Schubert, Z., Kiedy plakat śpiewał po polsku, Znak. Available at: https://www.miesiecznik.znak.com.pl/kiedy-plakat-spiewal-po-polsku-zdzislaw-schubert-polska-szkola-plakatu/, accessed: 09.01.2021

Pluta, E., unknown year, interview with Joostberens, Polska Szkoła Plakatu. Co z niej pozostało?. Avaliable at: https://www.swps.pl/strefa-designu/blog/19951-polska-szkola-plakatu-co-z-niej-pozostalo, accessed: 08.01.2021

Schubert, Z., 2001, Poles & posters, Print, 55 (2), 152-159

Strękowski, J., 2004, Jan Lenica: Film. Available at: https://culture.pl/en/artist/jan-lenica, accessed: 25.01.21

Victore, J. 1995, Poster master, Print (Archive: 1940-2005), 49 (5), 32-41

West, C., 2011, Poster Children, Print, 64 (4), 24-25

Zielinski, F., 1994, The rise and fall of governmental patronage of art: a sociologist’s case study of the Polish poster between 1945 and 1990, International Sociology, 9 (1), 29-41

Zwolińska, I., May 2018, Początki plakatu polskiego: Z ulicy na salony – o historii I procesie kształtowania się tej formy graficznej. Available at: https://grafmag.pl/artykuly/poczatki-polskiego-plakatu, accessed: 15.01.2021

Zwolińska, I., June 2018, Polski plakat na początku XX wieku: sztuka łącząca roozbity kraj. Available at: https://grafmag.pl/artykuly/polski-plakat-na-poczatku-xx-wieku-sztuka-laczaca-rozbity-kraj, accessed: 22.01.2021

Comments